Operating Environment

Global economy

The world economy, which had a lacklustre start in 2016, started on an upswing in the middle of the year and this momentum has generally continued into 2017. Growth in global GDP which recorded a low 3.2% in 2016, grew by 3.7% in 2017, and growth in 2018 is projected at 3.9%. A total of 120 countries, collectively accounting for three-quarters of world GDP, grew in year on year terms in 2017. Growth was better than previous forecasts showed in several advanced and emerging economies including the United States, Germany, Japan, Korea, Brazil, China, and South Africa. Many advanced economies are now approaching full employment. World trade picked up towards the end of the year driven by increased investment particularly in advanced economies and increased manufacturing output in Asia. However, the picture is not entirely rosy. Growth is still weak in many areas and political uncertainties; terrorism and climate change also pose risks.

The prices of fuel, which fell between February and August 2017, picked up in the last quarter of the year buoyed by the global growth, weather conditions in the US, production cuts by OPEC, and geopolitical tensions in the Middle East. Marker prices are expected to gradually decline over the next 4-5 years. Although short term economic forecasts are somewhat optimistic things look less rosy in the medium term. Possible downsides are increases in inflation and interest rates, protectionist policies, geopolitical tensions and political uncertainties. Furthermore, growth still remains weak in many areas. Nevertheless, the current environment has opened up opportunities which policy makers should capitalise on.

The US economy grew by 2.3% during the year. Corporate tax cuts are expected to stimulate growth through the next few years. Business and consumer confidence remains upbeat. With unemployment being at its lowest level since 2000, this should contribute to wage growth. Highly skilled and highly paid baby boomers becoming senior citizens in large numbers will slow the rate of labour force growth and consequently consumption growth. However, a substantial and sustained global upturn should stimulate increased economic activity through linkages to global value chains. Nevertheless, some uncertainties surrounding the policies of the current administration remain which may have a dampening effect.

The Chinese economy recorded a moderate growth of 6.5%. Growth was somewhat slowed down by policy makers seeking to rein in debt and factory pollution. The upside is that the changes should augur well for sustainable growth in the long term. The Indian economy is expected to record its lowest growth in four years (6.5%) in the year to March 2018. The economy was adversely affected in the short term by demonetisation and the Goods and Services Tax. GST and other structural changes augur well for the medium term. Other emerging economies in East and South East Asia were also boosted by increased external demand.

The US Dollar appreciated in real terms by 6% since August. The currencies of certain commodity exporters, including Russia, also appreciated reflecting improvement in commodity prices; on the other hand, the Euro, the Japanese Yen, and some emerging market currencies have weakened.

Low income countries continue to be faced with many challenges including diversifying their economies, maintaining growth while achieving the sustainability development goals, high debt levels and low commodity prices. Priority areas to address include broadening the tax base, improving debt management, reducing poorly targeted subsidies and improving infrastructure, health, and education. Climate change and extreme weather conditions, such as droughts in sub-Saharan Africa, pose threats to many countries. In low income countries a rise in temperature tends to lower per capita output both in the short and medium terms. Though sound domestic strategies and policies can help such countries will be unable to cope with the challenges without the assistance of the international community.

The Gulf region

All countries of the Gulf region have been adversely affected by the reducing oil price trend of the last three years but have nevertheless shown resilience. Growth has been reduced accompanied by widening fiscal and external deficits. Both OPEC and non-OPEC members have agreed to production cuts until March 2018 and there is a possibility of a further extension. There is optimism about stronger global growth resulting in higher demand and oil prices stabilising at around USD 55 per barrel in 2018/19. All GCC countries have to address the issues of reducing the oil dependence of their economies and cutting financing by the state. While this has led to fiscal consolidation it has weakened non-oil growth. The region is also affected by geopolitical risks.

A unified framework has been agreed on for the introduction of VAT within the GCC countries which will promote cross-border trade in the region. Although implementation was due to start from 1st quarter of 2018 it is likely to be delayed in most countries due to coordination issues and preparatory work requirements.

Bahrain has been adversely affected by low prices for both oil and bauxite. A moderate level of GDP growth has been maintained by deficit spending, at the cost of reduced reserves and increased public debt. The Kuwaiti economy grew by about 3% in 2016, boosted by higher oil production and government spending. Growth is expected to slow in 2017, but is expected to pick up in the medium term in the wake of increased oil production (and possibly higher prices) and infrastructure spending. Introduction of VAT in 2018 is on track, which should ease fiscal pressure.

Growth of the UAE economy, which recorded 2.3% in 2016, is expected to reduce further due to oil production cuts. However, investment that should take off to support the Expo 2020 event coupled with increased oil production as a fruition of oil field development should boost growth from 2018. The Expo event is expected to draw visitors in large numbers fuelling private consumption and services.

As with the rest of the GCC, Oman’s growth slowed down in 2016 and a growth of only 1% is forecast for 2017. Reduced government spending, low business confidence and private consumption is expected to slacken growth. Despite large spending cuts a budget deficit of 10%-14% is expected. With increasing interest rates monetary policy is expected to remain tight.

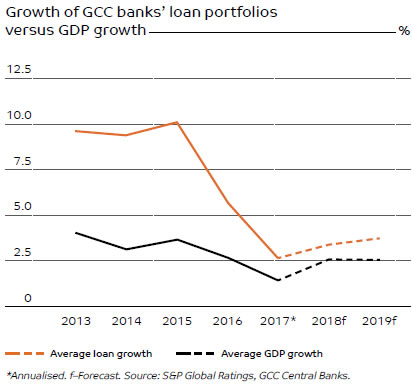

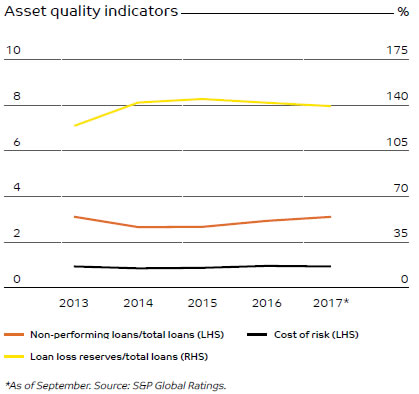

Coming to the banking and financial sector of the region, private sector lending which grew by 2.6% in 2017 on annualised average basis, is expected to grow by about 3-4% in 2018. This should be boosted by initiatives such as Dubai Expo 2020, the Saudi Vision 2030 and Kuwait 2035. The economic slowdown of the last two years caused a slight increase in non-performing loans. It is expected that the deterioration will continue for six months and then stabilise.

Growth in customer deposits slowed to 3.5% in the first months of 2017 compared to 5.0% in the corresponding period in 2016. Nevertheless, the GCC banks’ funding profiles can be broadly be considered satisfactory. Funding is largely from core customer deposits except for a few large wholesale customers. Loan to deposit ratios have been on an improving trend during the year. While the first nine months saw an increase in GCC banks’ profitability there are grounds for scepticism as to whether the trend will last. The increase has been due to banks deploying their excess liquidity in relatively high interest earning government bonds; a higher net interest margin due to improving local liquidity and increase in Federal Reserve’s interest rates; and aggressive measures of cost reduction. However, the trend is not likely to continue due to slower loan growth, higher loan impairment particular due to the implications of IFRS 9, and increase in operating costs due to the introduction of VAT.

The Saudi economy

The Saudi economy which grew by 1.4% in 2016 contracted by 0.7% in 2017 according to preliminary data. The main cause is the contraction in the oil sector, which is expected to be about 3%. The Kingdom complied with production cuts in 2017, which are due to last until March 2018. The Government’s efforts to diversify the economy have borne modest results with the non-oil sector expected to grow by 1%. Within the non-oil sector, a major contribution to growth will be from the non-oil mining sector, which is now the fastest growing sector in the Kingdom. Private ownership of residences is also expected to grow rapidly.

The fiscal deficit narrowed to 8.9% of GDP in 2017, from nearly 13% the previous year. This was mainly as the result of major steps taken to restore fiscal balance by way of cuts to civil service remuneration, affecting around two thirds of employed nationals, and reduction of subsidies. With reduced oil prices, the policies of the past underpinned by government employment, generous subsidies and free public services is becoming increasingly unsustainable. However, in April 2017 these measures were partially reversed with results coming in from other measures of fiscal consolidation.

The Kingdom successfully introduced Value Added Tax (VAT) from January 1, 2018 to be aligned with the GCC VAT framework. Saudi Arabia and the UAE have become the first countries in the GCC to introduce VAT. The rate will be 5%, but in accordance with the GCC VAT Treaty certain products and services will be exempt or entitled to zero rating. An excise tax of 100% will be levied on tobacco and energy drinks and 50% on soft drinks. From January 1, 2018, SAIB added VAT to all its products and services unless they came under the VAT exempt or zero-rated category.

The introduction of VAT is a necessary step to diversify the sources of government revenue in the context of falling oil prices. The practice of the past when citizens enjoyed generous subsidies while being free of taxes is no longer sustainable. While this will cause a slight rise in the cost of living, this will depend on an individual’s purchasing patterns. Citizens whose purchases are mostly of tax exempt goods will not be much affected.

A glimpse of the future face of the Kingdom was revealed at the Future Investment Initiative (FII) held in October 2017. This mega-event drew 3,500 leaders from the corporate, government and financial sectors and featured extremely high profile speakers. The cornerstone of the initiative is NEOM, a USD 500 billion giga-project which would be a business and financial hub extending over 26,500 square kilometres in the North Western region of the Kingdom. The thrust areas will be digital technologies, biotech, advanced manufacturing and energy making it a Silicon Valley of the Middle East. NEOM will be a partially autonomous region having its own customs, taxation and labour laws. In addition, there are plans to build an entertainment city in Riyadh and a resort destination on the Red Sea.

Vision 2030

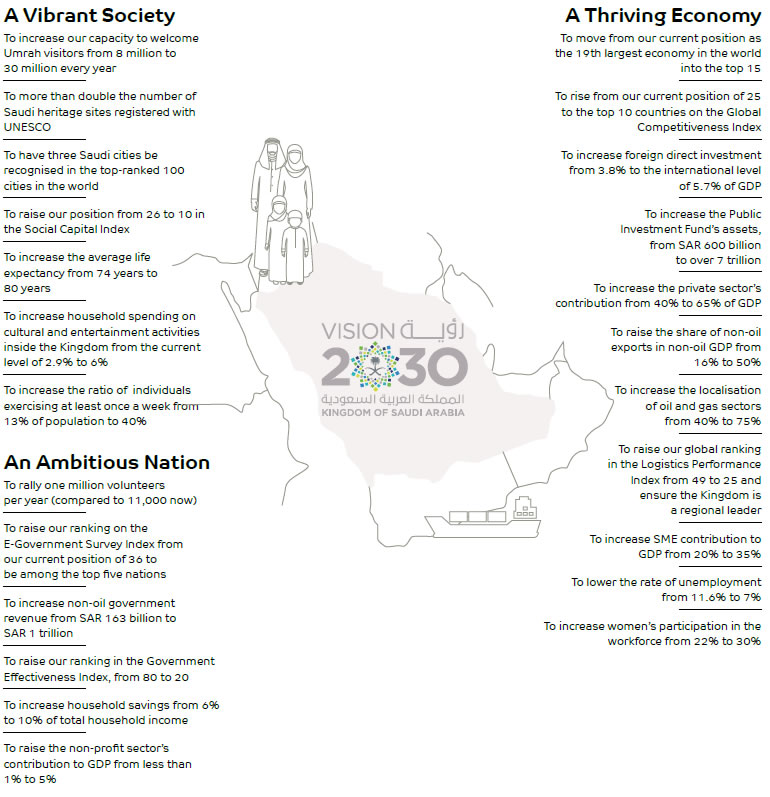

In April 2016 a visionary strategic plan for the future of the Kingdom was unveiled.

The Vision is built around three themes; a vibrant society, a thriving economy, and an ambitious nation. The members of a vibrant society would keep to their religious and cultural heritage while enjoying a good life in a beautiful environment with social protection. A thriving economy will create opportunities for all, by building an education system aligned with market needs. The nation’s ambitions will be achieved through effective, responsible, transparent, enabling, and high performing government at all levels.

The Vision envisages reducing the dependence on oil, expanding the role of the private sector in the economy and bringing Saudi Arabia into the top 10 slots in the Global Competitiveness Index. It targets an increase in non-oil revenue from SAR 163 billion to SAR 1 trillion. To meet the needs of the economy the education system will be revised to be aligned with the job market. A modern curriculum will be prepared focusing on rigorous standards in literacy, numeracy and character development. By 2030 The Kingdom aspires to have at least five universities in the ranks of the global top 200.The talents of Saudi women, which are at present an underutilised asset (over 50% of university graduates are women) will be brought on stream.

The role of the SME sector, which at present contributes only 20% to the GDP, is projected to expand. Young Saudi entrepreneurs will be encouraged with business-friendly regulations, easier access to funding, international funding and a greater share of national and government procurement bids.

The privatisation of state assets which is ongoing will be continued. The ownership of ARAMCO, the state oil giant, will be transferred to the Public Investment Fund and an Initial Public Offering is planned for up to 5% of the ownership. The revenue resulting from privatisation will be reinvested for the long term, in strategic sectors which require capital intensive inputs. In the process the economy of the Kingdom will be diversified away from excessive dependence on oil. Some of the thrust areas identified are localising renewable energy and industrial equipment sectors, developing leisure and tourism, investing in the digital economy and exploring and exploiting the non-oil mineral resources of the Kingdom. Saudi Arabia is endowed with many non-oil minerals such as, gold, silver, aluminium, copper, lead, zinc, iron ore, uranium and phosphate.

The service sectors will be opened up to private participation, shifting the government’s role to being more of a regulator. Banks and other financial service providers will adapt their products and services to the needs of each sector. The economic cities, projects, which have lagged in implementation, will be revitalised. The Kingdom will also create new economic zones in exceptional and competitive locations. Though the retail sector has flourished, it currently employs only 0.3 million Saudis out of a workforce 1.5 million and it is largely traditional retail. We intend to provide jobs for an additional million Saudis by 2020 and increase the contribution of modern retail and e-commerce.

To achieve its ambitious targets the Kingdom will need to identify and put in place best practices that will improve the efficiency and effectiveness of our public administration. This will include recruitment according to merit, human capital development and providing a conducive working environment.

In order to build the institutional capacities and capabilities needed to achieve the goals of Vision 2030 a National Transformation Programme 2020 was launched in 2016 with a four-year time frame. This sets interim targets within the framework of Vision 2030. The programme is intended to make a significant impact on planning efficiency and effectiveness as well as the integration of government action. The strategic targets and objectives for entities participating in the Vision 2030 will be identified. The strategic objectives will then be translated into initiatives, backed by detailed implementation plans and feasibility studies.

Partial achievement of some of the goals of Vision 2030 by 2020 is also planned. Some of these include:

- Creating at least 450,000 jobs in the non-governmental sector;

- The private sector to make a contribution of 40% towards funding of initiatives;

- Increasing localising at least SAR 270 billion of content which will reduce imports and create job opportunities;

- Build digital infrastructure and digital platforms to support government digital transformation.

The Saudi banking sector

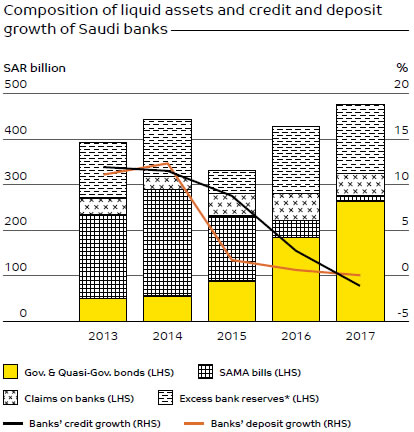

In 2017 Saudi banks achieved a very favourable liquidity position, with liquid assets standing at a record SAR 457 billion. This was despite slackening of deposit growth (growth was only 0.1% in the year) and unfavourable business conditions. Bank’s domestic liquid assets grew 11% in 2017 and accounted for 20% of total bank assets at year end. In another positive trend, Saudi banks’ reserves to total deposits notched 14.8% at end 2017, its highest in five years. The positive changes were achieved despite deposits remaining practically constant, by a 1.0% drop in banks’ loans (compared with a 3% increase in 2016) and a 43% increase in government bonds. The Bank’s holdings of domestic government bonds were SAR 254 billion at end 2017 compared with SAR 86 billion at end 2015. Successive issuance of debt by the Saudi Government, especially Sukuk issuance, provided an opportunity for banks to utilise their excess liquidity to purchase such high quality government investments.

*Excess bank reserves include cash in vault and deposits with SAMA in excess of statutory deposits.

Source: Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority monthly statistics bulletin

The reduction in oil prices has adversely impacted deposit growth which averaged 12% during 2012-2014. The lower oil prices caused decline in government balances, contraction in deposits from the private sector, payment delays and weakened economic growth all of which slackened deposits. However, the situation was somewhat mitigated when the government issued increased international debt which enabled a 12% increase in public sector deposit inflows as against a 10% decline in 2016.

The reduction in loans was mainly due to reduced economic growth (actually forecast to be a contraction) lower credit demand and banks’ reduced lending appetite. Loans declined especially in the building and construction sector (the sector suffered a drop of 15% in 2017), which is heavily dependent on government spending. The loan to deposit ratio stabilised at 86% at end 2017, 1% less than at end 2016.